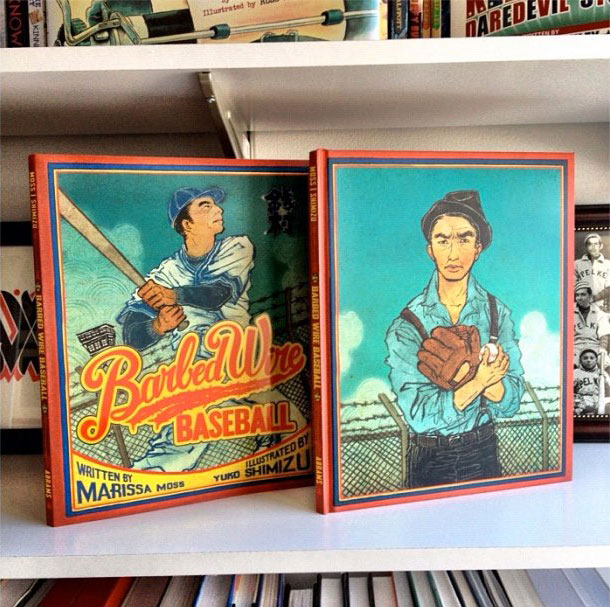

Barbed Wire Baseball Written By Marissa Moss Illustrated By Yuko Shimizu 2013

Abrams Books For Young Readers

Brilliant, brilliant book that presents a fascinating story

that is little known.

The subject of the

book is Kenichi “Zeni”

Zenimura (1900-1968). He is considered the father of Japanese-American

baseball, and he also popularized the game in postwar Japan. Zenimura was an extraordinarily

talented player who played all nine positions. He pitched right handed, but he

bat left handed.

Zenimura was born in Japan, and he moved to Hawaii when he

was 8 years old. There, he fell in love with baseball. After he graduated from

school, he moved to Fresno and formed a baseball team. In October of 1927, he

was one of four Japanese–American players picked to play in an exhibition game with the Yankees in Fresno. There is a photo of Zenimura standing in between Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig

that is reproduced in the artwork of the book. The actual photo appears in the

afterword.

When he was interred at the Gila River camp, Zenimura began

to covertly build a baseball field at the camp. When his efforts

escalated to the point that he was going out under the cover of night to steal

wooden posts from the camp fence so that he could build bleachers for the

field, the camp guards noticed. However, they observed that he we only taking

every other post, and thus leaving the structural integrity of the fence

intact. The guards did not raise the alarm. They quietly watched Zenimura.

Eventually, their position moved from quiet acquiescence to providing assistance

to the effort.

As Zemimura’s efforts grew, more and

more of the camp got involved. They pitched in to help weed the field, level

it, plant grass, make uniforms, and they become players and spectators.

I am especially impressed by the insight that is offered in

the artist’s note in the back of the book. I am always fascinated

by the way that the real, the imagined, and the fanciful all interact and come

together when non fiction stories are recounted in picture books. This

illustrator’s notes are highly unusual because they present this

interaction as its central theme.

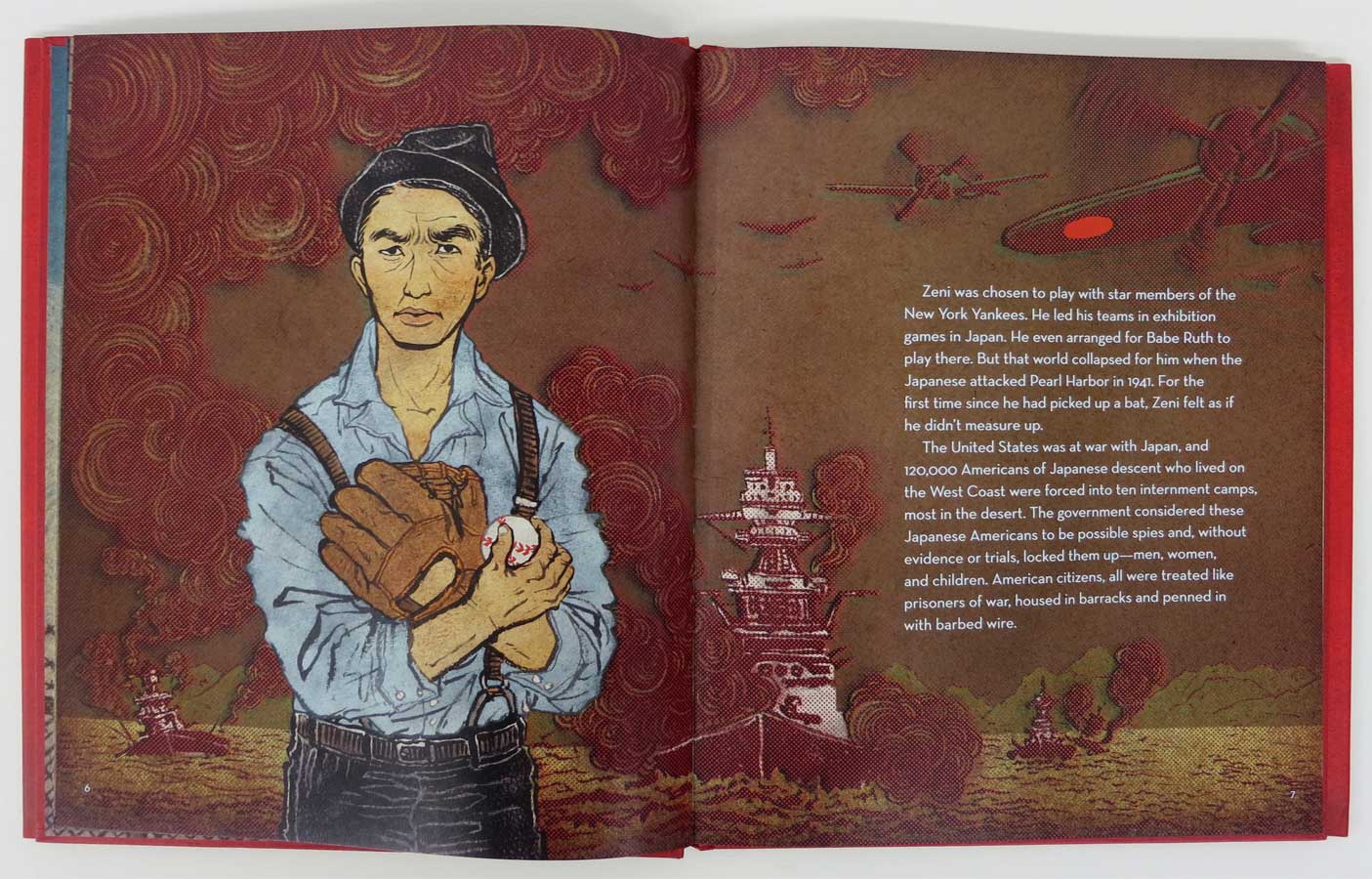

The artist notes that while barbed wire was present at the

early stages of the camp, it was later removed. He decided to maintain it in

the illustrations in order to stress the fact that the camp was indeed a prison

for those who were held there.

There are almost no photos of Zenimura during his

concentration camp years. Actually there is one that was shot from distance in

order to show the field. Zenimura and son appear in this photo, but the

distance is too far to make out their features. The artist had to use photos of

Zenimura from before the war to provide the model for his face.

I also appreciate the fact that the artist shares with us

that while he did extensive research on the Gila River camp in order to depict

it accurately, he also used photos from other camps in creating the art.

He could not find any visual images of the teams’ uniforms, so he adapted a homemade uniform from the period as a pattern, and he applied

a bit of artistic imagination.

It is all too rare that we get such insights into how the

creative process informs the depiction of nonfiction presentations.

The art is extraordinarily striking. Very stark and

engaging, and yet with a fantastic range of expression preserved. There are

elements of collage, older Japanese art styles, and a hint of Chinese

propaganda poster style. The effect is very visually impactful, and it brings

home the fact that this is a prison camp being depicted.

In emphasizing the starkness of the camp, the art highlights

the humanity of the people held within.

Highest possible recommendation!

By all means, use in conjunction with “My

Dog Teny” .

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.